In the latter half of his article, Borenstein turns his attention towards critiquing the argument that bitcoin miners improve grid stability by acting as demand response resources, also known as controllable load resources.

For those who aren’t familiar, “demand response” refers to an energy consumer who adjusts the amount that they consume based on the amount of demand elsewhere in the power grid. For example, during a peak demand period, a miner who acts as a demand response resource would reduce or fully power off their operations so that the energy they would have consumed can be used to meet demand elsewhere in the grid.

In a 2021 report, the International Energy Agency (IEA) stated:

“…faster progress is needed: 500 GW of demand response should be brought onto the market by 2030 to meet the pace of expansion required in the Net Zero Emissions by 2050 Scenario (NZE), a tenfold increase on deployment levels in 2020.”

Miners are particularly well suited to being demand response resources because they are location independent (you can set up miners right next to generators in remote locations), can rapidly adjust their power consumption (powering fully on/off in ~15 seconds), and electricity is the main operating expense for miners so they are naturally incentivized to reduce load when electricity gets more expensive during peak demand periods.

Borenstein doesn’t directly refute these ideas, but he takes issue with miners receiving payments for the times when they turn off because he believes that miners will game the system to receive larger payments by artificially increasing their baseline energy consumption leading up to demand response events in order to receive larger payments when they shut off. He sees these payments as unnecessary given that miners don’t want to be online when electricity prices are high anyway.

However, the stat that Borenstein cites to justify this position is outdated and extremely inaccurate. He states, “30% to 40% of crypto mining electricity usage is for fans and other cooling technologies that can suck up power on demand,” a stat which he pulled from a 2017 article by Digiconomist.

In reality, mining data centers are optimized to use as little energy as possible for cooling, as electricity costs typically account for the majority of their operating expenses. The best metric for measuring this is Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE), which measures the ratio of energy used to power actual servers (in this case, mining machines) relative to all other sources of electricity consumption in the data center. According to the University of Cambridge,

“Conversations with miners support the hypothesis that mining facilities generally have significantly lower PUE than traditional data centres. In a best-case scenario, mining facilities have optimised data centre operations to a point where there is nearly zero overhead. This scenario is represented by assuming a PUE of 1.01.”

We can isolate the energy consumption for non-mining loads from the PUE value with the equation: Cooling Power = (PUE – 1) * Power Consumed. In other words, a PUE of 1.01 indicates that the power consumption of cooling technologies would account for only 1% of total consumption. Even if we are extremely conservative and assume that the PUE of 1.01 is an entire order of magnitude off and the true amount of consumption for cooling is 10% (a very inefficient and likely uncompetitive mining operation), it’s still 3-4x lower than the figure cited by Borenstein via Digiconimist.

On top of that, we would be remiss not to mention that Digiconimist is not a credible source of information. The site is run by Alex de Vreis, an employee of the Dutch Central Bank whose methodologies for estimating bitcoin’s energy consumption have been thoroughly discredited and whose original focus for the site was actually to blog about Dogecoin, an alternative cryptocurrency to bitcoin which ironically also uses proof of work.

In summary, Borenstein’s point that miners will manipulate their energy consumption to maximize demand response payments is based on an extremely flawed statistic from an unobjective source.

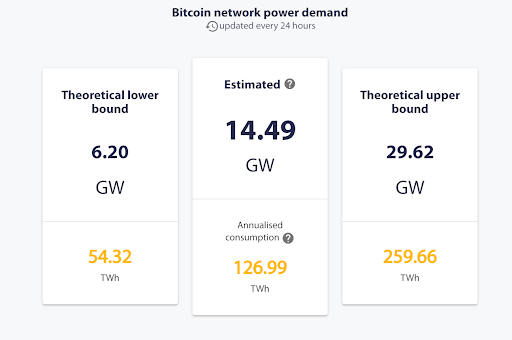

However, he didn’t get everything wrong. Borenstein finishes by saying that “paying crypto mining for demand response is likely to encourage more crypto mining,” and that part does make sense. Considering the IEA’s report that we need 500 GW of additional demand response brought to market by 2030 (34.5x the total estimated consumption of the bitcoin network today), we don’t think that encouraging more crypto mining is such a bad idea.